By Helen Norman, Rose Smith and Jeremy Davies

25 May 2023

Research shows that parents’ engagement in activities that promote their children’s learning – such as reading and playing – can bring huge benefits to children’s educational development. Parental participation in ‘school-involvement activities’ – everything from helping out in the classroom, to fundraising or being a school governor – can also have benefits because this demonstrates the value and importance of education to the child, which can have a positive influence on learning, behaviour and attendance (Campbell 2011). Parental school involvement is therefore an important first step that can lead to or enhance parental engagement at home. Yet our study finds that overall, fathers are only half as likely as mothers to take part in such activities.

Across all the school-involvement activities measured by the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) – a nationally representative survey of households that surveys children in the middle of primary school at age 7 – just under a third (32%) of fathers said they participated in their child’s school in some way, compared to more than three-fifths (61%) of mothers.

The gender gap is even more marked for certain school-involvement activities: mothers are about four times more likely to help in the school library or classroom, or be a member of a parent association, committee or group for example. In some of the activities, less than 5% of fathers contribute. For more detail, see Table 1 below.

Table 1: What activities do parents do in their children’s school at age 7?

| Activity | % of fathers involved | % of mothers involved |

| Help with fund-raising activities | 23 | 41 |

| Help out in elsewhere in the school e.g. library | 7 | 30 |

| Help out outside of class with special interest groups like drama/sports | 6 | 6 |

| Some other activity* | 5 | 5 |

| Be a member of parent association, committee or group | 4 | 16 |

| Help out in class | 4 | 20 |

| Be a member of management board/governing body | 3 | 5 |

*Some other activity includes help with upkeep/running of school, help with breakfast club/afterschool, help with courses for school and general help

Note: Some parents took part in multiple activities. Based on 4047 households

What do we know about dads who do get involved?

Having established that fathers are less likely to get involved in school-participation activities, we wanted to find out more about the ones who do get involved.

We looked at fathers participating in one or more of the activities listed in Table 1, when their children were aged 7[1]. We found that dads were more likely to be involved at school:

- If they were frequently engaged in childcare activities at home: for example, playing with toys, drawing and painting or going to the park

- If their children had good grades in their Key Stage 1 Assessments

- If they were from a more affluent household (defined as having a household income that was more than 60% of the UK median, after housing costs);

- If they were in paid work; and

- If they were educated to at least degree level.

We also found differences according to ethnicity: for example, fathers of children from a Pakistani or Bangladeshi background were less likely to get involved with their child’s school compared to fathers of children from white backgrounds.

These findings suggest that barriers to fathers’ school involvement may relate to income, time, work, educational and/or cultural background.

Why do more mothers get involved?

We found that the same barriers that affect fathers’ school involvement hinder mothers’ school involvement. Yet despite this, mothers are much more likely to get involved at school compared to fathers. Why?

Research suggests that the societal expectation that mothers take the main responsibility for children’s care and education continues to dominate despite some shifts in social attitudes about gender roles (e.g. see Curtice et al 2020). For example, research with equal and primary caregiver fathers has found that even when fathers do equal shares of everyday aspects of care and school support, mothers remain the ‘educational executives’ who took primary responsibility for the important decisions about their child’s schooling – like coordinating and managing school activities, and monitoring their educational progress (Brooks and Hodkinson, 2022).

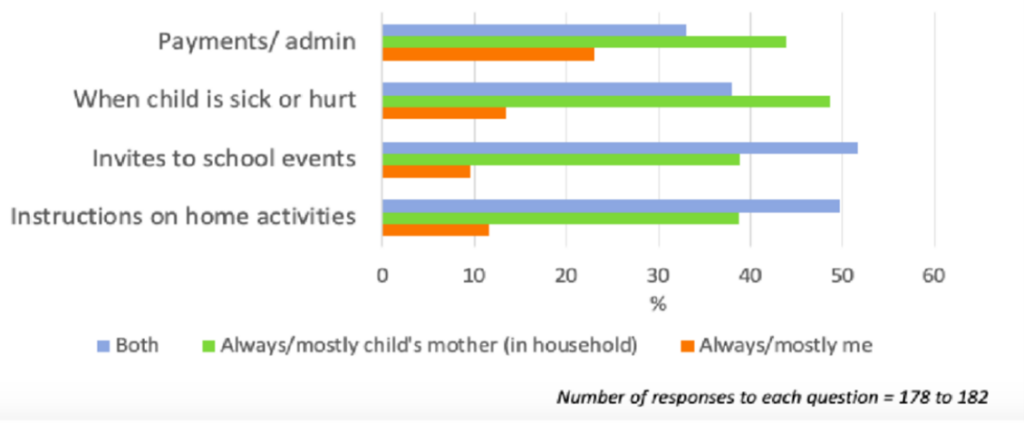

This maternal ‘primary responsibility’ role may be perpetuated by schools and childcare providers, who tend to position the mother as the primary carer and first point of contact despite the father’s main or equal caregiver status. Our own survey of UK fathers found a sizeable proportion of childcare providers and schools mostly or only contacting the mother about various aspects of school life, including sickness, homework and payment of bills (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Who does the school, nursery, pre-school contact most frequently about…

How can we help schools to engage fathers?

The assumption that mothers are (or should be) primarily responsible for managing and coordinating children’s care and education, may act as a barrier to fathers’ participation in school-involvement activities, helping ensure that on average fathers do less.

Schools could help to engage fathers by addressing them directly in their communications, providing resources and activities that encourage dads to participate and running father-targeted events.

It’s worth remembering that fathers (and mothers) do not all have the same time and resources to support children’s education, and that individual and structural inequalities exist amongst different parent groups according to socio-economic status and ethnicity (Parentkind, 2021).

Designing school-involvement activities that can be done from home and do not eat up time and money (including journeys to and from school, which may be expensive) might be preferable for working fathers (and working mothers) – allowing them to engage at different times that can fit around their work schedules. This approach may be especially effective for parents on lower incomes and those who work longer hours.

Schools could also try to implement inclusive strategies to engage fathers from different cultures, for example promoting activities in partnership with local mosques.

Why is this important?

Direct engagement with fathers is important, because if they get involved at school, it demonstrates clearly to the child the value and importance of education. They are also more likely to engage in positive ways in the child’s learning, guided by the school’s resources and recommendations. This may have beneficial effects on children’s development and behaviour over the longer term – as set out in our earlier blog.

Fathers’ greater participation in school-involvement activities could also help shift perceptions around who is primarily responsible for caregiving, thus reducing the burden for mothers and contributing to greater gender equality in the division of care more broadly.

References

Brooks, R. and Hodkinson, P., 2022. The distribution of ‘educational labour’ in families with equal or primary carer fathers. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 43(7), pp.995-1011.

Campbell (2011) How to involve hard-to-reach parents: encouraging meaningful parental involvement with schools, Research Associate Full report, National College for School Leadership: Nottingham. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/340369/how-to-involve-hard-to-reach-parents-full-report.pdf

Curtice, J., Hudson, N. and Montagu, I. (eds.) (2020), British Social Attitudes: the 37th Report, London: NatCen Social Research.

Goodhall, J., Montgomery, C. (2014) Parental involvement to parental engagement: a continuum Educational Review, 2014 Vol. 66, No. 4, 399–410.

Norman, H., Davies, J. Packman, K. and Lewis, S. (2022), What a difference a dad makes: engaging with fathers as well as mothers, Parentkind. https://www.parentkind.org.uk/about-us/news-and-blogs/blog/what-a-difference-a-dad-makes-engaging-with-fathers-as-well-as-mothers

Parentkind (2021) Blueprint for Parent-Friendly Schools: https://www.parentkind.org.uk/For-Schools/Blueprint-for-Parent-Friendly-Schools

[1] We did this through logistic regression – a statistical method for exploring the relationship between different variables. We used MCS data that had been linked to the National Pupil Database so we could measure attainment in Key Stage Assessments at age 7.

Dataset for the linked MCS-NPD: University College London, UCL Institute of Education, Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Department for Education. (2021). Millennium Cohort Study: Linked Education Administrative Datasets (National Pupil Database), England: Secure Access. [data collection]. 2nd Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 8481, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-8481-2